Mark R. Sneed, Taming the Beast: A Reception History of Behemoth and Leviathan (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2022). 288 pages. ISBN: 9783110579314.

Reviewed by Dr Rod Benson

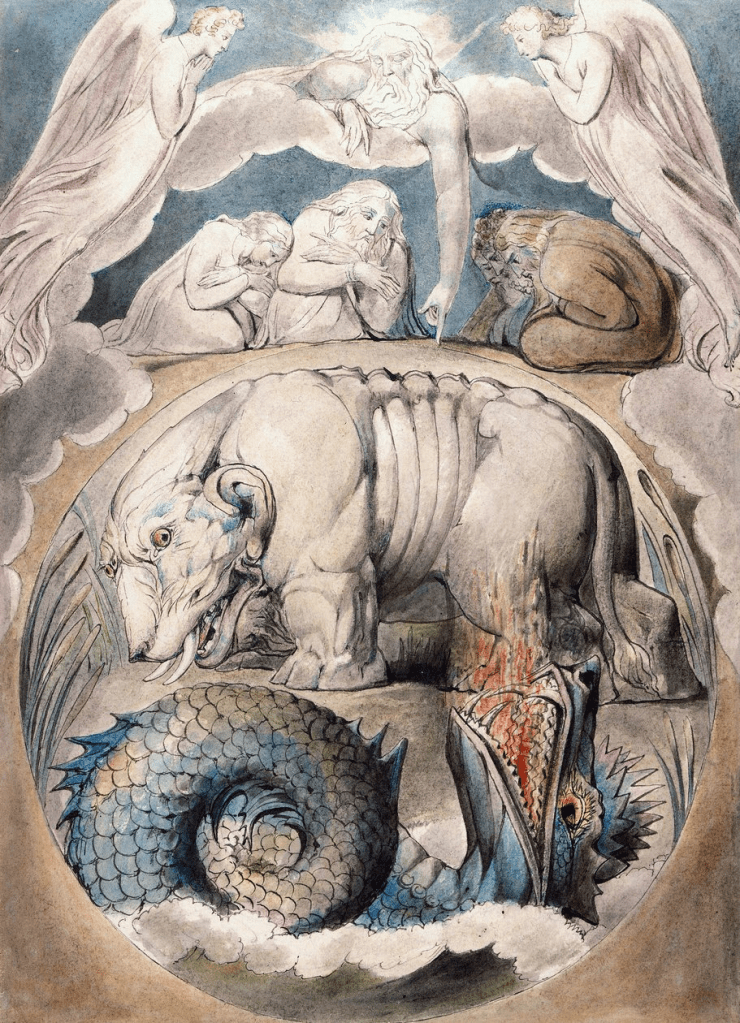

The poet and artist William Blake painted the image above, depicting the mythical biblical creatures Behemoth and Leviathan, in 1805. More recently, children’s books such as Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are and movies like Monsters Inc. have domesticated the monsters we feared as children, but there are still plenty waiting to be tamed.

Mention of monsters in the Bible is rare, but scholars have been identifying and taming them for centuries. Mark Sneed’s Taming the Beast presents a fascinating new account of how this taming has occurred, focused on two monsters mentioned in the Book of Job.

The Hebrew Bible introduces us to four mythical monsters: Leviathan (Jon 3:8; 41:1-34, 12; Ps 74:14; 104:26; Isa 27:1), Tannin (sea monster, Job 7:12; Ps 74:13; Isa 27:1; Ezk 29:3; 32:2), Rahab (lit. “boisterous one”; Job 9:13; 26:12; Ps 89:10; Isa 30:7; 51:9), and Behemoth (Job 40:15-24). There are mentions of other strange terrestrial creatures, especially in apocalyptic literature, but these four are identified by name.

As the blurb notes, Sneed’s investigation raises fascinating questions: Why are Jewish children today familiar with these creatures, while Christian children know next to nothing about them? Why do many modern biblical scholars follow suit and view them as minor players in the grand scheme of things?

Conversely, why has popular culture eagerly embraced them, assimilating the words as symbols for the enormous? More unexpectedly, why have fundamentalist Christians touted them as evidence for the cohabitation of dinosaurs and humans?

Leviathan and his “side-kick” Behemoth are given extended treatment in the penultimate chapters of Job. Originally gargantuan and terrifying sea creatures representing disorder and chaos, and possibly evil, Sneed suggests that both monsters are presented as agents of theodicy (p. 2). There are parallels with the creation story of Genesis chapter 1, with divine power mastering the watery chaos typical of the beginning of time and space.

Sneed first outlines the need for a reception history approach to the topic. By this he means how different cultures and communities have modified the meaning of the biblical texts through such acts as transmission, translation, reading, retelling, and preaching.

He draws connections between biblical monsters and the wider literary traditions of the ancient Near East, and links biblical monsters with later theodicies and “sociodicies” (that is, legitimation of contemporary power structures and challenges to them).

He traces the origins of the reconfigurations of the biblical monster myths as the appropriation and epitome of evil, and further traces their later interpretation by Christian theologians from Origen to Barth.

There is even a chapter on culinary interpretations of the monsters – eating monsters versus monsters eating us. Sneed also discusses the “great fish” in the Book of Jonah, Herman Melville’s mythic white whale, the Axis Mundi tradition, and the shift to the portrayal of Leviathan as a whale or crocodile, and Behemoth as a hippopotamus.

Then, in a chapter titled “Return of the repressed,” he examines Romantic perspectives (Blake, Milton, Robert Alter, and portrayals in film). In his conclusion, Sneed presents the results of his wide-ranging research under nine headings.

A terrific read.

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.