Alasdair MacIntyre, one of the world’s great twentieth-century philosophers, died on Wednesday. He is best known for reintroducing virtue ethics as a viable alternative to consequentialism. He also saw his faith and his philosophy as mutually enriching.

Reading the obituaries, I was reminded of this quotation from one of MacIntyre’s twenty books:

Man is in his actions and practice, as well as in his fictions, essentially a story-telling animal … But the key question for men is not about their own authorship; I can only answer the question, ‘What am I to do?’ if I can answer the prior question, ‘Of what story or stories do I find myself a part?’[1]

MacIntyre argues that we can only know and do what is ethical if we participate in a grand metanarrative, a story bigger than ourselves. One of the great privileges open to us, living in this time and this place, is to participate in the ongoing story of Jesus. The Beatitudes, the list of short statements that preface the Sermon on the Mount, are a map outlining our path home, and a compass showing us the way.

Today we are reflecting on Beatitude 2, “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted” (Mt 5:4).

We see mourners at a funeral. Tears of grief also come to those who are unemployed, or laid aside by illness or injury, pain, hunger, injustice, or those with the weight of the world on their shoulders. Tears of grief come to the bullied, the slandered, the misunderstood, to those promoted to their level of incompetence, who long for retirement.

Tears of grief come to the shell-shocked who sit on the doorstep of their bombed-out home in Ukraine, to those who stand today in the rubble of a Gaza apartment building, to those who walk homeless in the rain past a fancy Sydney restaurant as those inside avert their gaze.

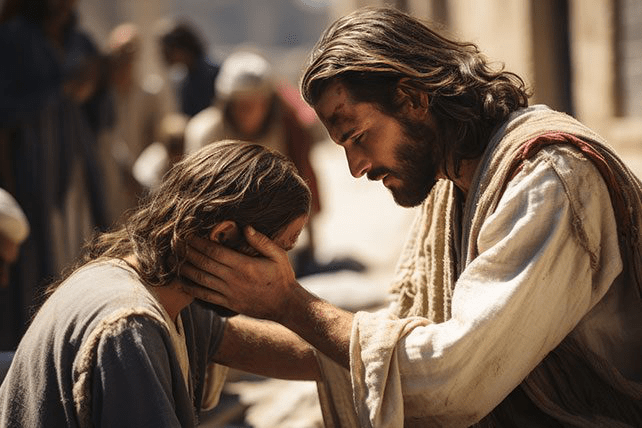

Jesus declares all such people “blessed,” and promises that they will be comforted.

In each of the Beatitudes, Jesus refers not to individuals but to people groups. He does not specify what it is that they are mourning: he simply offers them comfort. We grieve our losses and our failures in our own ways, but we grieve in solidarity with others who have sustained loss and experienced the consequences of failure. We are not alone. And God sees our tears, and hears our prayers.

In this Beatitude, Jesus echoes the words of Isaiah 61:1, “The Lord has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to heal the broken-hearted…”

It is not those who have dried their eyes, and tightened their belts, and engaged the tools of positive thinking who are blessed here. Rather, it is those who are currently experiencing real sadness and loss. The paradox is that happiness, or deep-seated wellbeing, comes to such people in the midst of their grief. It is possible for deep joy to coexist with deep grief. Jesus sits with us in our grief and our pain.

We know God’s faithfulness; we experience God’s love. As we participate in the story of Jesus, we trust God to bring ultimate justice and peace. And so we carry on, one day at a time.

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

New Testament scholar Michael Green says that those who mourn are happy because “they have seen the depth of the world’s suffering and of their own sin, and it has broken their hearts.”[2] Another scholar, Frederick Bruner, writes, “It is those for whom sadness is deep that God is real.”[3]

In his commentary on this text, evangelical writer John Stott suggests that the mourning is not the result of bereavement but of repentance. He limits the Second Beatitude to spiritual poverty – to a loss of innocence, a dearth of righteousness, and a lack of self-respect brought on by sin and by sinning.

Scripture certainly encourages us to examine our hearts, our lives, and to seek forgiveness and healing from whatever is of the dark side within us through confession and contrition. Naming what is bent in us, and expressing sorrow for the way things are, are two early steps on the path to healing and wholeness.

When the first Christians shared the good news with others, they urged them to practice repentance toward God, and to put their trust in the Lord Jesus Christ (see Ac 20:21; cf Mk 1:15).

If you were able to see your sins, your failures, spread out on a table in front of you, what would you do? You would most likely mourn, weep and wail. There would be sorrow. There would be shame. There might be horror, and remorse.

The first step in healing and wholeness is to take a long, hard look at what is wrong, at what needs to change, at what needs to be mortified and done away with, and then resolve to walk the narrow road (cf Col 3:1-10; 2 Cor 7:9-11). This is repentance, and it is often accompanied by tears. But repentance is a precious seed that bears beautiful fruit. The Eastern Orthodox writer Frederica Mathewes-Green (b. 1952) suggests that

repentance enlarges the heart until it encompasses all earthly life, and the sorrow tendered to God is no longer for ourselves alone. Knowing our own sin, we pray in solidarity with all other sinners, even those who hurt us. With all creation we groan, crying out to God for his healing and mercy.[4]

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

In his beautiful book, Lament for a Son, Nicholas Wolterstorff writes:

Who then are the mourners? The mourners are those who have caught a glimpse of God’s new day, who ache with all their being for that day’s coming, and who break into tears when confronted with its absence. They are the ones who realise that in God’s realm of peace there is no one blind and who ache whenever they see someone unseeing. They are the ones who realise that in God’s realm there is no one hungry and who ache whenever they see someone starving. They are the ones who realise that in God’s realm there is no one falsely accused and who ache when they see someone imprisoned unjustly. They are the ones who realise that in God’s realm there is no one who fails to see God and who ache whenever they see someone unbelieving. They are the ones who realise that in God’s realm there is no one who suffers oppression and who ache whenever they see someone beat down. They are the ones who realise that in God’s realm there is no one without dignity and who ache whenever they see someone treated with indignity. They are the ones who realise that in God’s realm of peace there is neither death nor tears and who ache whenever they see someone crying tears over death. The mourners are aching visionaries.[5]

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.”

There are tears of contrition, and there are tears of empathy. Empathy is the heart of practical Christian ministry. Psychologist Carl Rogers defined empathy as the “accurate perception of another’s internal frame of reference,” and viewed this as an essential quality for personal growth and change. Elon Musk famously claimed that empathy is “the fundamental weakness of Western civilization.”[6] That sounds like the opposite of what Jesus would say.

We are not all naturally empathetic, but empathy is a skill that can be learned. I don’t have to experience another person’s experience to comprehend how it is for them. American educator Stephen Covey suggests that empathetic listening is

listening with the intent to understand … You look out through [the other person’s] frame of reference, you see the world the way they se the world, you understand their paradigm, you understand how they feel … When you listen with empathy to another person, you give that person psychological air.[7]

Jesus was an empath par excellence. He could read hearts; he could perceive a person’s internal frame of reference. He responded to human need with empathy, patience and love.

“Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.” Not forgotten, sidelined, laughed at, trampled on, condemned, and written off, but comforted, their internal frame of reference validated and their whole being held in the merciful embrace of Jesus.

God is in the business of comforting all who mourn. Such people, says Jesus, are blessed (see also Rev 7:15b-17; 21:3f).

Sermon 809 copyright © 2025 Rod Benson. Preached at North Rocks Community Church, Sydney, Australia, on Sunday 25 May 2025. Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are from The Christian Standard Bible (Nashville: Holman Bible Publishers, 2020).

References

[1] Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue (second edition; Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984), 216. The obituary is available here, accessed 23 May 2025.

[2] Michael Green, The Message of Matthew (Leicester: IVP, 1988), 90.

[3] Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary. Volume 1: The Christbook: Matthew 1-12 (revised and expanded edition; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 164.

[4] Frederica Mathewes-Green, The Illuminated Heart (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2001), 38-42.

[5] Nicholas Wolterstorff, Lament for a Son (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1987), 85f.

[6] Elon Musk, interview, The Joe Rogan Experience, February 2025.

[7] Stephen Covey, The 7 Habits of Highly Successful People (second edition; New York: Pocket Books, 2004/1989), 240f.

Image source: https://churchleaders.com