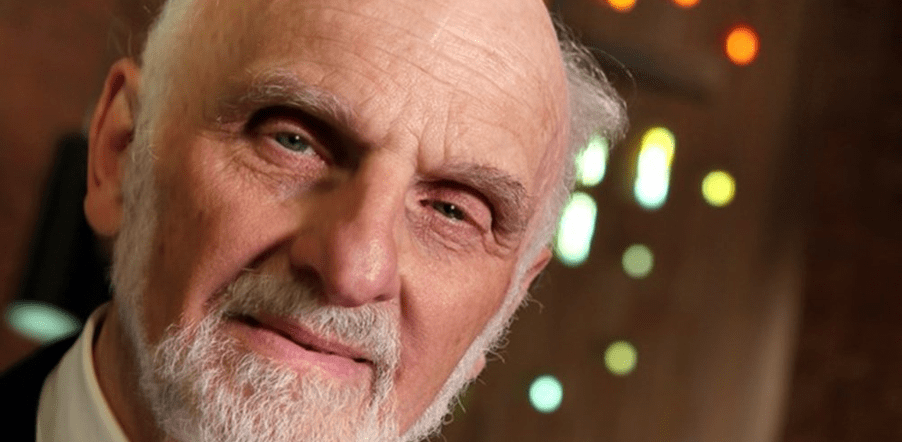

Walter Brueggemann, one of the great Protestant theologians of the Hebrew Bible, died on Thursday, aged 92. Brueggemann is widely described as a modern prophet in the tradition of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible.

He possessed the ability to explain the meaning of the ancient text with clarity and precision, and interpret its prophetic challenge in ways that confront, challenge and inspire action for justice and peace in our world today.

In his book, Reality, Grief, Hope: Three Urgent Prophetic Tasks, Brueggemann writes: “The prophetic tasks of the church are to tell the truth in a society that lives in illusion, grieve in a society that practices denial, and express hope in a society that lives in despair.”[1]

It has always been so, yet never more urgently than today. In a society, and a culture, that thrives on illusion, denial and despair, the church is called to speak truth, to model the practice of grieving for what is lost, and to instil hope through beloved community.

You and I are the church. Together, we constitute the church of Jesus Christ, the hope of the world. These are the tasks to which God calls us, for which Jesus prepares us, and for which the Spirit empowers us for active service in the world.

As I read the Beatitudes, the eight short statements introducing the Sermon on the Mount, I hear the voices of the Hebrew prophets. I hear the echo of those voices in the prayers and preaching of the first followers of Jesus. I hear their resounding echo in the speech and writing of countless truth-speakers, grief-expressers, and hope-announcers down through the centuries to our time.

And so here we are, in 2025, listening again to the teaching of Jesus: “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled” (Mt 5:6).

This is the fourth of four consecutive Beatitudes expressing various elements of our dependence upon God. The remaining four Beatitudes show how we work out such dependence practically, in our life in the world.

Notice that Jesus does not congratulate “the righteous” in Matthew 5:6 but those who possess an appetite for righteousness. We’ll get to what that word “righteousness” means in a few minutes.

I would not want to pray the first three Beatitudes, but I would pray this one. I wouldn’t want to ask God to make me “poor in spirit,” or sorrowful; I might occasionally ask God to make me more humble. But it is surely right to ask God to increase my “hunger and thirst for righteousness.”

Matthew uses the verb “to hunger” nine times in his Gospel, and only here is it a metaphor. In speaking of “hunger and thirst for righteousness,” Jesus does not mean an occasional interest but an intense longing. For those he has in mind, it’s a lifestyle, a calling. It’s not mere situation that Jesus is talking about, but aspiration and mission.

It’s not good to be starving and dying of thirst, but it is good to be hungry and thirsty for the life of the kingdom, for the kind of world Jesus calls us to shape, a world where mercy, justice and peace prevail.

To pray this Beatitude is to recognise that we cannot achieve such a vision by ourselves. We need divine help, divine intervention. The remedy and satisfaction come from beyond our own resources, from a merciful and gracious God. Our God simply asks us to depend upon him, to pray for positive change, and to be willing and ready to participate in his mission.

Not long after this mountain-side experience, Jesus says to his apprentices, “Seek first the kingdom of God and his righteousness, and all these things will be provided for you” (Mt 6:33). But what does Jesus mean by “hunger and thirst for righteousness,” or “seek first … the righteousness of God”? New Testament scholar Frederick Bruner observes that “Classically, Protestants have found Jesus Christ in his grace more deeply in ‘the Fifth Gospel,’ the Gospel according to Paul.”[2]

That is usually our default approach when interpreting the meaning of the Beatitudes. We could call it the “evangelistic” approach. But there is also a “discipleship” approach.

Another New Testament scholar, Scot McKnight, suggests that if our theology of salvation is shaped predominantly by the letters of Paul, we tend to focus on the “gift” approach, toward the imperative of being declared righteous by faith in Christ.

On the other hand, a “Torah observance” approach (also known as the covenant-faithfulness approach) to our theology of salvation interprets “righteousness” in verse 6 (and in verse 10) as “behaviour that conforms to God’s will.”

In other words, Matthew’s use (and Jesus’s use) of “righteousness” here is not about the way in which a person adopts Christian identity (salvation as a gift from God separate from behaviour), but how they express what it means to follow Jesus in daily life (salvation as the imitation of Christ and faithfulness to his teaching).

Despite the fact that he is writing his Gospel decades after Jesus taught the Sermon on the Mount, Matthew employs the Torah-observance approach in many places. A fine example of this approach is Joseph, the legal father of Jesus, who because he was righteous in the Torah-observance manner chose to divorce Mary because he wanted to remain observant (Mt 1:19).[3]

This is the Jewish theological world in which Matthew and Jesus lived. Paul’s Greek theological world takes the Jewish notion of righteousness in another direction – not a wrong move, but a different emphasis and a different trajectory.

The “gift” view emphasises God’s grace and understands “righteousness” as “right standing before God.” We find ourselves starving for God’s grace, and thirsting for “the water of life” (Rev 22:1, 17), and in his mercy God satisfies our longing and saves us.

The “behaviour” view emphasises adherence to the Jewish Torah and understands “righteousness” as conformity to God’s will as expressed in Scripture, or simply as faithfulness to God’s covenant with Israel. Taken this way, we become apprentices to Jesus and begin to walk the narrow path of Christian discipleship, and our hunger and thirst for the Way of Jesus is satisfied as we conform to his image and witness the unfolding of the kingdom of God in our communities.

In both cases, salvation is not earned but requires effort, hence the idea of hungering andthirsting for righteousness. Such people

long for what is right, they crave justice, they cannot live without God’s victory prevailing; for them right relations in the world are not just a luxury or a mere hope but an absolute necessity if they are to live at all.[4]

At the same time, we miss the intent of the message of Jesus if we think of the Beatitudes solely as a demand for right conduct and not also a declaration of congratulations for the coming of the kingdom of God in the here and now, in the spirit of Isaiah 61:1.

Indeed, as the evangelical New Testament scholar Leon Morris puts it, “How could anyone have a strong desire for a right standing before God without at the same time strongly wanting to do the right?”[5] The happiest of people are those who have a passionate desire to be right with God and stay that way, bringing pleasure to God and healing to their world through vital Christian practices.

Sadly, the satisfaction of this hunger and thirst is often incomplete in this life, and in this “vale of tears.” The good news is that, for those who follow his Way, Jesus promises “absolute and utter satisfaction: they will find a kingdom society where love, peace, justice, and holiness shape the entirety of creation.”[6]

In his long poem, “From the rising of the sun,” Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz asks a question:

When will this shore appear from which at last we see

How all this came to pass and for what reason?[7]

He’s acknowledging an awareness of human experience as an incomplete journey, as inexplicable and unfinished business. He’s also expressing the deep yearning of our souls for knowledge and understanding, for homecoming, and for lasting satisfaction.

Living as we do in the now-but-not-yet of the kingdom of God, the words of Jesus are profoundly consoling, hopeful, and empowering: “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they will be filled.”

Sermon 811 copyright © 2025 Rod Benson. Preached at North Rocks Community Church, Sydney, Australia, on Sunday 8 June 2025. Unless otherwise noted, Scripture quotations are from The Christian Standard Bible (Nashville: Holman Bible Publishers, 2020).

References:

[1] Walter Brueggemann, Reality, Grief, Hope: Three Urgent Prophetic Tasks (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2014).

[2] Frederick Dale Bruner, Matthew: A Commentary. Volume 1: The Christbook: Matthew 1-12 (revised and expanded edition; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004), 169.

[3] Scot McKnight, Sermon on the Mount (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2013), 44.

[4] Bruner, Matthew, 169.

[5] Leon Morris, The Gospel According to Matthew (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 99.

[6] McKnight, Sermon on the Mount, 44.

[7] Czeslaw Milosz, “From the rising of the sun,” in Selected Poems 1931-2004 (ed. Robert Hass; New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 106.

Image source: Church Times