In his writings, the Australian Baptist theologian G. H. Morling occasionally refers to “great souls,” people of extraordinary humanity or spiritual insight – those rare individuals able to express uncommon empathy or magnanimity, whether in actions or words.

The phrase “great soul” echoes the classical Greek notion of megalopsychos, the “great-souled man,” articulated by Aristotle, denoting largeness of spirit.[1] In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle uses the term to describe a moral ideal rather than an emotional temperament. The “great soul” is the person who rightly judges themselves worthy of great honour. For Aristotle, honour is the highest external good, and the megalopsychos stands in proper relation to it: neither grasping nor indifferent, neither arrogant nor falsely modest.

The great-souled person exhibits a settled excellence of character (aretē). Such a person is calm, measured, slow to anger, and independent of petty concerns. They are generous with benefits but reluctant to receive them. Their speech is restrained, their posture dignified, and their ambitions proportionate to their virtues. Importantly, megalopsychia is not self-assertion detached from moral substance but expresses the full range of ethical virtues—justice, courage, temperance, and practical wisdom.

Aristotle’s “great soul” therefore represents moral maturity: a harmony between self-knowledge, moral worth, and social recognition. It is a demanding ideal resonant of dignity, self-respect, and the ethics of honour within a well-ordered life. As well as being applied to Christian mystics, the concept has been applied to spiritual masters such as Buddhist bodhisattvas, Hindu rishis, and Sufi saints, where it similarly refers to personal qualities of spiritual depth, moral gravity or expansive compassion.

Morling was familiar with this use of the term. He distinguishes physical suffering (and an associated emotional “heart suffering”) from spiritual suffering. He speaks of the spiritual suffering of “great souls” who imagine themselves as “permanent misfits” in their world. He refers to melancholy moods observed in texts from the Hebrew Bible such as Psalm 37 and the Book of Job.

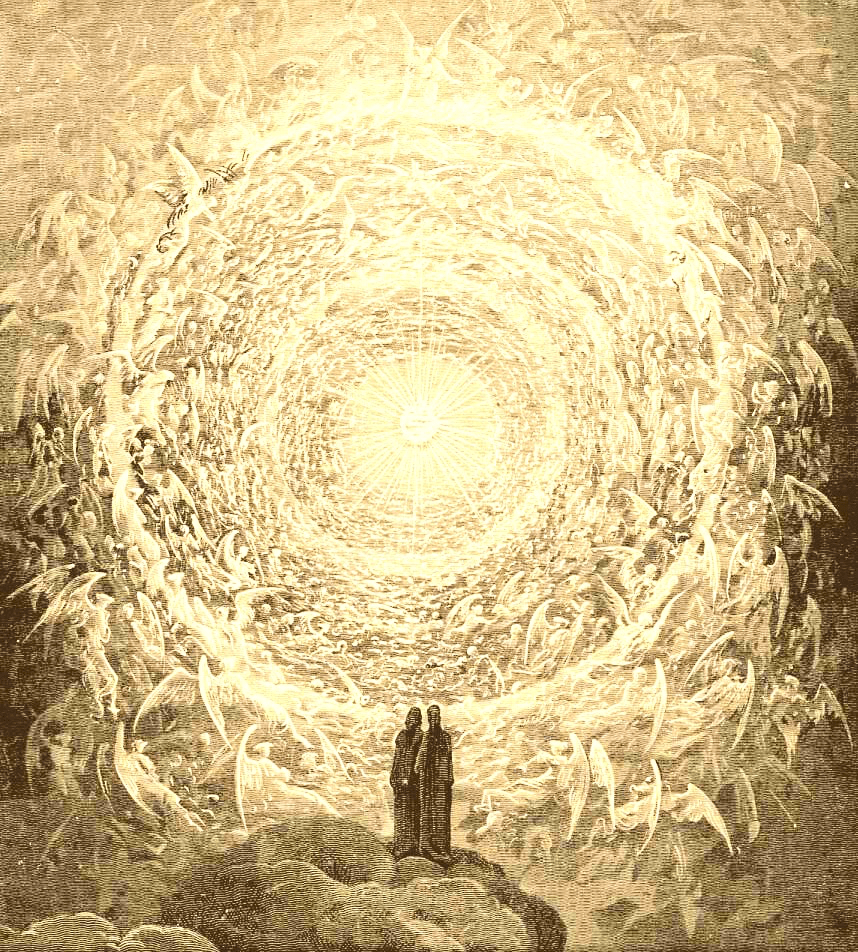

Throughout Christian history, mystics have been recognised as “great souls”: women and men whose lives display an unusual depth of prayer, moral seriousness, spiritual authority, and love for God and neighbour. The phrase does not imply spiritual elitism. Rather, it names a particular amplitude of soul that stretches the boundary of the Christian imagination of what faithful human life might be. The “great soul” possesses a largeness of vision, charity, endurance, and attentiveness to God that brings peace and hope to suffering or bewildered humanity.

Christian mystics are “great” because they more fully inhabit our ordinary existence. Their mysticism is rarely a flight from classic theology or moral responsibility but rather intensifies these commitments. The mystic’s prayer leads not to detachment from the world but to a deeper participation in it: compassion sharpened by contemplation, courage sustained by silence, and action shaped by communion with God. For example, Teresa of Ávila’s ecstatic prayer produced institutional reform; Julian of Norwich’s visions yielded a theology of hope; Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s contemplative discipline sustained costly resistance.

What marks such figures as “great souls” is not merely extraordinary human experience but deep spiritual integration. Doctrine and devotion, intellect and affection, suffering and hope are held together within a coherent life oriented toward God and offered to bless others. Their writings often feel expansive rather than constricting, inviting readers into freedom, humility, and love rather than fear or competition.

The language of “great souls” also helps resist a reduction of Christianity to technique, moralism, or institutional maintenance. Mystics remind us that the deepest resources of the human spirit lie not in novelty or control, but in holiness, patience, and attentiveness to the transforming presence of the divine. They shape the horizon of ordinary discipleship. Their lives function sacramentally, making visible what grace makes possible through a fully yielded human life.

G. H. Morling was regarded by some as a Christian mystic, although elsewhere I have debunked that notion as wishful thinking. There is no indication that he thought of himself as a “great soul.” His use of the term may have arisen from his devotional Christian reading. The late nineteenth century saw many compilations of aphorisms, adages and quotations from the works of famous Christian thinkers and mystics, and these were naturally considered to be the writings of “great souls.” For example, the energetic Boston-based compiler Mary Tileston selected and arranged several anthologies of Christian quotations, one of which is titled, Great Souls at Prayer.[2]

Morling was fond of using quotations to illustrate and emphasise his teaching, and quoted from many of the authors featured in this publication, although there is no evidence that he owned a copy of this book. On the other hand, he was a fine preacher and public speaker, and some of his sayings deserve to be recorded and shared to inspire and challenge future generations.

Rev Dr Rod Benson is General Secretary of the NSW Ecumenical Council and a Uniting Church minister at North Rocks Community Church, Sydney. His PhD thesis explored the Christian thought of G. H. Morling.

References

[1] See, e.g., Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. W. D. Ross, in Jonathan Barnes (ed.), The Complete Works of Aristotle: Revised Oxford Translation. Vol. 2 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 1767-1776.

[2] Mary W. Tileston, Great Souls at Prayer (London: Allenson & Co., 1898).

Image source: Liberty Community Online