George Fox (b. July 1624, d. 13 January 1691), the English dissenter and founder of the Religious Society of Friends (commonly known as the Quakers), was one of the most creative and disruptive figures in post-Reformation church history. Emerging from the turbulence of seventeenth-century England with its civil war and sectarian ferment, Fox’s life and teaching invite Christians from various traditions to ask what it means to actively listen to God, follow the demands of conscience, and seek to practice religious beliefs without coercion.

The son of a Leicestershire weaver, Fox was apprenticed to a shoemaker at the age of 12. He found the English Civil War (1642-51) morally intolerable, and in 1643 left home, travelling for several years in search of enlightenment. Fox came to the view that only Jesus Christ, and not the church or its ministers, could “speak to [his] condition,” and taught dependence on the “inner light” of the Spirit for inspiration and guidance. In his book, The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), William James called him a “once-born soul” – one whose life was marked by an underlying sense of harmony and confidence in the goodness and nearness of God. Salvation, for Fox, appears to have meant the freedom to live a holy life as God had intended for Adam.

Though neither trained in theology nor ordained by the established Church, Fox was a compelling public speaker and successful organiser. In 1652, Fox climbed Pendle Hill in Lancashire and experienced a vision of a “great people to be gathered.” A short time later, he was preaching to large crowds attracted by his enthusiasm and moral earnestness. He formed his most zealous followers into a stable organisation, the Religious Society of Friends, whose origin is often dated to Fox’s 1652 Pendle Hill experience.

Many of Fox’s “converts” were drawn from other nonconformist traditions. Indeed, Baptist historian Leon McBeth claims that Fox may have drawn many of his converts, and much of his teaching, from the General Baptists (the Arminian-leaning Baptist alternative to the Calvinistic Particular Baptists).[1] Fox was also keen to expand his movement beyond England, travelling to promote and encourage the establishment of Friends’ meeting rooms in Ireland, the West Indies, North America, Holland and Germany.

Among other distinctives, Fox taught that there was no need for priests as intermediaries with God, or as interpreters of Holy Scripture. He challenged the deep alignment between church and power that shaped much of European Christianity. He held that worship should be centred not on ceremonial performance but on attentive waiting: silence, prayer, and the readiness to speak only when prompted by the Spirit.

He interrupted the preaching of Anglican ministers by quoting Scripture during their sermons. This drew the enmity of the Church of England and Fox was imprisoned eight times on religious and other grounds. On one occasion, a magistrate pejoratively called his supporters “quakers” after Fox exhorted him to “tremble at the word of the Lord” (Isaiah 66:5), and the label stuck.

Fox also had a strong belief in the potential of the human spirit. He held that the “seed of God” enabled holiness, and that what he described as “that of God” was present in every person, granting access to an infinite ocean of divine light and love. Spiritual growth required attention to the “light within” through silent reflection or meditation, alone or in small groups. This practice led to the formation of regular local meetings of Friends for (mostly) silent reflection, and continues to profoundly shape the movement today. On the other hand, his opposition to the arts, and rejection of formal theological study, forestalled development of these practices among Quakers for many years.

The American poet Walt Whitman, whose parents were inspired by Quaker principles, wrote that “George Fox stands for something too – a thought – the thought that wakes in silent hours – perhaps the deepest, most eternal thought latent in the human soul. This is the thought of God, merged in the thoughts of moral right and the immortality of identity. Great, great is this thought – aye, greater than all else.”[2]

In the last years of his life, Fox continued to participate in the London Meetings and to lobby Parliament about the persecution of Friends. The new King, James II, pardoned religious dissenters jailed for failure to attend the established church, leading to the release of about 1,500 Friends. The Act of Toleration (1689), passed two years before Fox’s death, enabled dissenters to freely worship and laid the legal basis for the religious freedom enjoyed by many countries today.

From an ecumenical perspective, Fox’s critique of the status quo reminds all Christians that structures, rites, and doctrines may harden into barriers if they cease to serve the living encounter with Christ. At the same time, his emphasis on inward experience may resonate with the doctrine of theosis, or direct participation in the life of God, while warning against subjectivism detached from communal discernment and the wider Christian story.

Fox’s ethical commitments continue to resonate. In 1651, he was offered a commission with the English army, but refused on the ground that “he lived in the virtue of that life and power that took away the occasion for all wars.”[3] Later Quaker testimonies on peace, justice, equality, and care for the poor, drawing on Fox’s insights and emphases, have shaped abolitionist movements, conscientious objection to war, and humanitarian reform.

His insistence that every person bears the image of God converges with Catholic social teaching, Protestant ethics, and Orthodox understandings of human dignity. His call to “let your lives speak” parallels the biblical insistence that faith without works is dead. Movements for prison reform began in England among Quakers. In the 17th-century campaigns against the slave trade, William Wilberforce described Quakers, among others, as “my staunchest allies.”

Quakers have long made significant contributions to the ecumenical movement, not least in Australia, and Fox’s legacy raises questions for ecumenical theology and praxis. How do churches hold together sacrament and Spirit, biblical authority and individual freedom, doctrine and experience? How do Christians discern the Spirit’s voice amid competing claims? How can communities pursue reform without erasing tradition? To engage Fox is to engage these questions honestly, across confessional boundaries.

George Fox invites the church to return to the living Christ who is present in Scripture, encountered in devotion, discerned in community, and embodied in acts of love. His life reminds us that authentic spiritual renewal is expressed in a patient, humble willingness to be converted anew by the God who continues to speak in meaningful ways to ordinary people.

The Church of England, which once had him imprisoned to suppress his religious enthusiasm, now honours Fox on 13 January, the date of his death in 1691.

Further reading:

Pink Dandelion, The Quakers: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Jean Hatton, George Fox: The Founder of the Quakers (Oxford: Monarch Books, 2007).

H. Larry Ingle, First Among Equals: George Fox and the Creation of Quakerism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996).

John L. Nickalls (ed.), The Journal of George Fox (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952).

Quaker Faith and Practice (fifth edition; London: Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain, 2013).

Rev Dr Rod Benson is General Secretary of the NSW Ecumenical Council and a minister of the Uniting Church of Australia serving at North Rocks Community Church. This is the first of a series of articles on prominent leaders whose legacy has shaped ecumenically-minded Christian traditions.

References

[1] H. Leon McBeth, The Baptist Heritage: Four Centuries of Baptist Witness (Nashville: Broadman Press, 1987), 155.

[2] Walt Whitman, “George Fox and Shakespeare” in “November Boughs,” Prose Works (Philadelphia: David McKay, 1892), available at https://www.bartleby.com/lit-hub/prose-works/22-george-fox-and-shakspere/

[3] “George Fox,” https://www.quakersintheworld.org/quakers-in-action/12/George-Fox

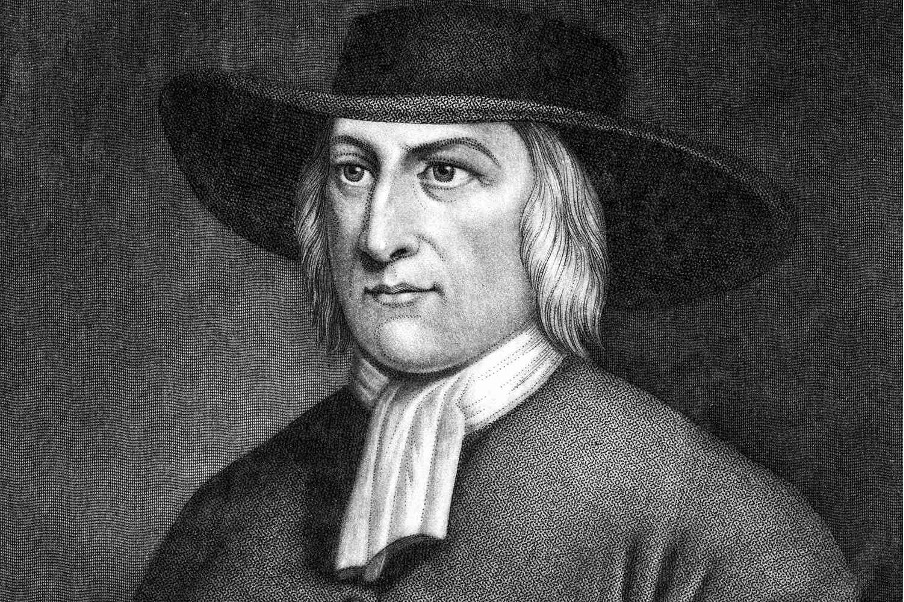

Image source: George Fox. Image from an 1872 engraving. Getty Images. There are no known contemporary sketches or paintings of Fox’s likeness.