As I said in the first post in this series, none of the churches I attended as a child affirmed creeds or confessions of faith. The Bible alone was said to be our rule of faith. While I remain grateful for the spiritual tradition that shaped me, I have come to appreciate the legitimate place of creeds and confessions for personal guidance and for use in the community of faith.

Why this change? If the Bible is the final or supreme authority for our theological beliefs, why make a place for creeds? Is the Bible somehow inefficient or incapable of establishing and commending Christian belief?

All Christian churches accept that creeds and confessions of faith possess an authority subordinate to the unique authority of Scripture. Some churches, like those of my childhood, do not in practice recognise the authority of creeds, just as other churches dispute the generally agreed supreme authority of the biblical writings. But that is a topic for another day.

Creeds and confessions of faith seek to summarise Scripture. They aim to succinctly express core biblical doctrines. They have a limited ambit. They don’t reach beyond Scripture, they don’t serve as commentaries on Scripture, and they don’t give expression to human experience. They merely testify to the truths of the Bible as understood by classic orthodox Christianity.

However, in expressing biblical doctrine in concentrated form, the creeds possess a singular power. As theologian John Webster observes, as well as functioning as a kind of oath of allegiance, a creed or confession “is that event in which the speech of the church is arrested, grasped, and transfigured by the self-giving presence of God.”[1]

Moreover, creeds and confessions are not personal statements by autonomous individuals but systematic summaries of the content of Scripture as understood and appropriated by the church in community. Anglican priest and theologian Michael Leyden argues that

The corporate nature of doctrines – that they articulate the Church’s faith – means that they are also the benchmark by which Christians in every generation measure their speech about God, looking back to what has gone before to make sense of what is happening now because the triune God is consistently God’s self in all encounters with human beings.[2]

Creeds and confessions, then, speak with authority for and on behalf of the church. They are carefully formulated and agreed to by a specific community at a specific time. They are intended to be universally applicable statements of doctrine. Alteration and addition to creeds and confessions of faith are therefore rare and subject to intense scrutiny and deliberation before adoption.

Such statements are also usually, though not universally, binding on members of affirming faith communities. Exceptions include non-credal churches such as many Baptist churches and associations (see No creed but the Bible), and churches that formally dissent from a specific doctrine in a creed such as non-Trinitarian churches and those that reject the filioque phrase added to the text of the Christian creed by the Western Church in the Middle Ages.

As early as the second century CE, Christians were using the term “rule of faith” (Regula Fide) for commonly agreed doctrinal statements. The Latin regula translates the Greek word kanon, meaning “rule” or “measure.” Biblical scholar Luke Timothy Johnson points out that it is not accidental that the term “canon” was used to identify both Christian Scripture and Christian creeds.[3]

The “rule of faith” has served every generation of Christians as a standard of orthodoxy and as a guideline for interpreting Scripture and evaluating theological teachings. Although creeds and confessions of faith do not provide commentaries on the biblical text, they do seek to ensure that readings of Scripture remain within the boundaries of Christian orthodoxy, limiting the unintentional rise of heresy.

The heritage of creeds and confessions of faith possessed and promulgated by the universal church reflects the critical importance of Scripture as the foundation for all Christian belief. These classic documents confirm the central place of apostolic tradition and its continuity in Christian preaching and teaching and help to ensure that progress in Christian doctrine remains faithful to the apostolic witness and therefore to the mission of Jesus Christ.

Neither salvation nor Christian identity depend on adherence to credal beliefs. On the other hand, if a church, or a person professing Christian faith, cannot affirm the classic ecumenical creeds, there is a good chance that they are not yet Christian in the classic sense. Creeds possess an authority subordinate to the unique authority of Scripture, but it is not an independent authority.

Dr Rod Benson is Research Support Officer at Moore Theological College, Sydney. He previously pastored four Baptist churches in Queensland and NSW, and served for 12 years as an ethicist with the Tinsley Institute at Morling College.

References

[1] John Webster, Confessing God: Essays in Christian Dogmatics II (London: T&T Clark, 2005), 71.

[2] Michael Leyden, Faithful Living: Discipleship, Creeds and Ethics (London: SCM Press, 2019), 16.

[3] Luke Timothy Johnson, The Creed: What Christians Believe and Why It Matters (New York: Doubleday, 2003), 46.

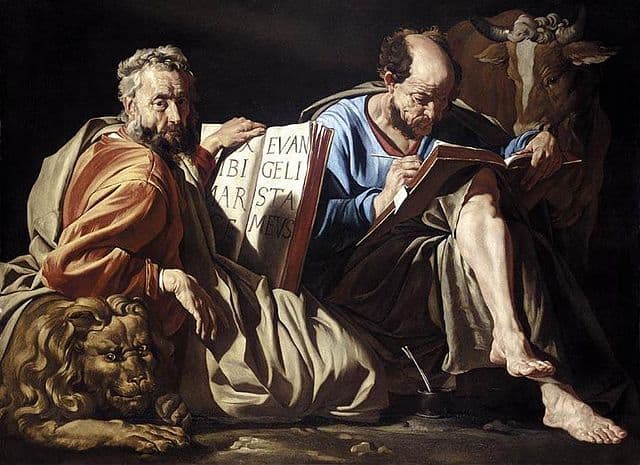

Image source: Wikimedia Commons.